The state of our railways - How did we get here and how do we get back on track?

On Monday, Azaria Howell reported in the NZ Herald, that in Wellington “replacing trains with buses on maintenance days is expected to be the norm for at least a decade, as the region works through a renewals backlog.” Meanwhile, in Auckland, disruptions continue on the rail network, which is undergoing a major rebuild ahead of the City Rail Link opening sometime in 2026. With all this negative coverage in the news, it’s important to discuss how these challenges have come about, why it is strategically important to fix them, and how we do that.

How did we get here?

Rail in New Zealand has a fairly mixed history but this is particularly true if you focus on the last 30 to 50 years. Corporatisation and transition to a State Owned Enterprise through the 1980s saw reductions in services and reduced investment in maintenance. This accelerated with privatisation in 1993, which saw an asset-stripping approach taken by the owners1. This period of decline, along with there having been no significant rail investment in Auckland urban rail since 1930, almost led to the closure of the Auckland Rail network for passenger trains in the early 1990s and was narrowly saved through some shrewd decision-making. This would have been disastrous for our largest city, constraining the growth of the city that has accelerated since the early 2000s. The revival of the City Centre, particularly downtown around Britomart, would have been muted at best and the impending city centre bus capacity issues would likely have already struck.

In a 2023 episode of The Detail, Dr Andre Brett explains this history “We've had decades of under-investment in the rail network and policies that since the 1950s have focused very single-mindedly on roads. That's not going to be turned around overnight," he says.” While some growth projects have recently occurred, particularly in Auckland with double tracking of the Western Line, construction of the Manukau Branch and network electrification, the underlying issues that come from decades of little maintenance or renewals in the rail lines themselves have been building.

The historic lack of investment in maintenance and renewals has been particularly apparent in Auckland over the last few years with the major disruptions including:

Six months of disruptions including full shutdowns for weeks at a time after damage to rails through rolling contact fatigue led to cracks in the rails and 130km of rails needing to be replaced.

Since December 2022, the Rail Network Rebuild has been underway, replacing kilometres worth of the formation below the rail lines, that had largely not been renewed since the lines were originally built, some of which from the 18. Firstly, with a three-month closure of the Onehunga and inner section of the Southern Line, followed by a nine-month closure of the Eastern Line.

So far in 2024, there have been many days of reduced service and speeds due to heat restrictions. This is in part due to the increased risk of heat misalignment due to recent works on the Auckland rail network.

The systemic underinvestment in rail makes the forecast of “10 to 15 years” of disruption, and little weekend service, projected for Wellington of little surprise. Like Auckland, there has been no significant investment for decades and a growing backlog of maintenance. There is no singular point of failure, rather it is a systemic issue with the approach to rail in New Zealand. Though it is also worth noting the parallels in under-investment in maintenance across all infrastructure, as covered in Business Desk, the Infrastructure Commission’s latest report shows that NZ has $287b of infrastructure to maintain but doesn't. This is just one example of this historical underinvestment coming to a head.

Why does this matter?

Our urban rail systems, along with the limited remaining inter-urban freight and passenger lines, are of significant strategic importance for our country for several reasons.

Rail is critical for providing high-capacity public transport access to city centres in Auckland and Wellington, which play a critical role in our economy with GDPs of $30.4b and $24b as of March 2023 respectively2. It is difficult and expensive to deliver the capacity required through buses.

Supporting the growth of our cities, particularly new residential housing being enabled through the National Policy Statement on Urban Development (NPS-UD), see the example below.

Supporting emissions reduction and transport resilience through providing an alternative to driving and more freight on our roads.

Despite the challenges and historic under-investment the 2021 Value of Rail report estimated the total value of rail in New Zealand to be $1.70 billion - $2.14 billion each year, through reduced congestion, reduced greenhouse gas emissions and air pollution and improved road safety.3

What is the pathway forward?

Getting ahead on the maintenance backlog requires funding and short-term pain for long-term gain. Auckland’s Rail Network Rebuild, while painful for users, was a positive step forward on this. Especially ahead of the City Rail Link opening, which will see increased train frequencies across the network. Similar measures to accelerate the rebuild and required $1.6b in network maintenance across the Wellington network need to be considered.

Allowing this to drag out for 10 to 15 years will counter many aims of local and central government including mode shift and housing enablement. People are going to be less convinced about buying or renting near a rail line if they don’t think they can depend on it. Continual weekend shutdowns will almost certainly harm the Wellington City Centre, including by making events at the Cake Tin less accessible for those coming from suburbs further out. When further shutdowns do occur, it will require a more concerted effort to improve the bus replacement alternatives. Auckland Transport has done this quite well during the rebuild of the Eastern Line in 2023 while benefiting from resiliency in the regular bus network.

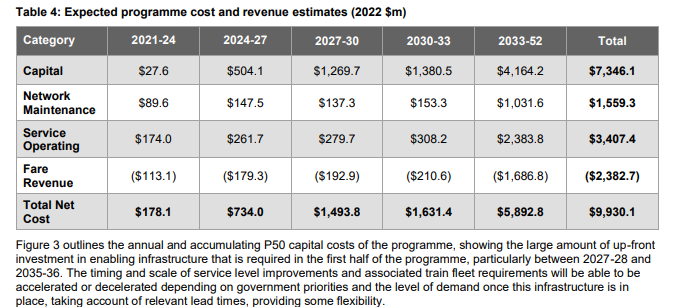

If an accelerated pathway can be found, there are efficiencies from building for growth during the required rail shutdowns. The Wellington Rail Programme Business case was completed in 2022, identifying the actions required to support growth over the next 30 years. If we are serious about the strategic role of rail in our urban centres, and minimising disruption, then we should look to deliver at least some of the initial priorities identified in the Wellington PBC, as part of the rebuild. These priorities could include:

Build a 4th main into Wellington Station, allowing for greater separation of Hutt Valley and Kapiti Line services, improving resiliency and frequency.

Upgrading signalling, presumably to European Train Control System (ETCS) Level 2, to allow higher frequencies.

Bypass the single-track bottleneck north of Pukeura Bay, see map below, with a new two-track tunnel to improve resilience and remove barriers to capacity and frequency improvements.

Further stages of the PBC could occur later including the construction of a third main line through Tawa Valley, grade separation of rail crossings, and station upgrades, particularly to improve accessibility and amenity. There is not a single lift on the Wellington Rail Network and many of the ramps to access stations are not at gradients suitable for wheelchairs. Investments like this go hand-in-hand with the development the NPS-UD is enabling along the rail lines.

Conclusion

Rail already plays a critical role in both Wellington and Auckland and is set to only grow in importance with current policy, particularly around housing growth. However, both have been facing significant disruption in recent years with no clear end point, where reliable year-round service will be provided. This is highlighted in Auckland where rail patronage is lagging far behind bus and ferry in the post-covid recovery due to the disruptions. In Auckland, CRL Day One will be a major step forward for the city but will highlight the other major investments required to maximise the capacity of the network. These include the 3rd and 4th main from Westfield to Pukekohe, introducing ETCS level 2, level crossing removal, and grade separation of flat junctions.

We need to find ways to deliver maintenance and renewals with less disruption and when disruption must happen, maximise the return through increased investment in improvements alongside the maintenance. This will not be cheap but is the cost of inaction for decades. The required rebuild of Wellington’s rail network should be evaluated for an accelerated programme, which seeks to maximise the return from disruption and shorten the project from the 10 to 15 years currently projected.

Smith, P (2008). NZ buys back rail network for $520m. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/04abe542-1a48-11dd-ba02-0000779fd2ac

Infometrics (2023). Auckland City Centre Economic Profile https://ecoprofile.infometrics.co.nz/Auckland%20City%20Centre/PDFProfile#h2

Infometrics (2023) Wellington City Centre Economic Profile https://ecoprofile.infometrics.co.nz/Wellington%20CBD/PDFProfile#h2

KiwiRail (2021). Value of Rail report. https://www.kiwirail.co.nz/who-we-are/about-us/value-of-rail/

and what about rail in Christchurch and Dunedin, and say between Napier and Hasting, Auckland and Hamilton . . .