All aboard! Five practical steps for queer safety on public transport

This is a guest post by Transport Planner Kiri Crossland. It was originally published on LinkedIn.

Getting on a bus should be as easy as simply getting on a bus. But for queer people, this apparently simple act is full of often invisible barriers.

Since 2022 it’s been my mission to understand these invisible barriers and what it means for queer people’s access to public transport. This mission has involved a Master of Environmental Planning which I've recently completed at The University of Waikato and I’ve been sharing what I’ve learned along the way here, on LinkedIn.

In this part of the story, I’m looking at how safety (or the lack of it) impacts queer people’s access to public transport. My online survey showed that queer people feel less safe on public transport and this affects how often they use it.

Why don't queer people feel safe?

A large factor in feeling unsafe is experiencing harassment and discrimination. For the straight participants, discrimination was very rare, while for queer people it was a relatively common occurrence. The graph below shows just how stark this difference is.

There was also a disparity in how often queer and straight people experienced harassment, although this was less pronounced. Queer people experienced harassment at greater rates than straight people, which affected how safe they felt.

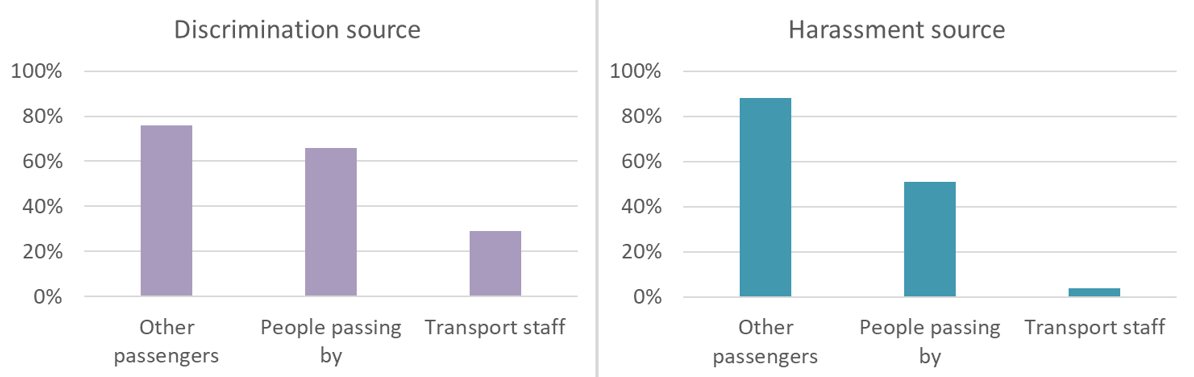

I also collected data about where this discrimination and harassment is coming from. The results show that most discrimination and harassment towards queer people comes from other passengers, or people passing by stops or stations. A smaller amount of each comes from transport staff. This is important as the source of discrimination and harassment influences what we can do about it.

How can we improve safety?

The statistics don't paint a very nice picture, but there are plenty of things we can do to change that. There are five key areas where we can influence queer feelings of safety:

1. Frequency improvements

This is a bit of a unicorn intervention as it will improve access to public transport for everyone. When public transport runs at frequencies of at least 10-15 minutes people don’t have to rely on a timetable, they can just turn up and know that a service will be there soon. For queer people, this has the added benefit of reducing their exposure time to discrimination and harassment from people passing by, by cutting the amount of time they have to wait. The majority of queer participants (88%) said frequency improvements would make them feel safer.

2. Staff training

From the survey results, we can see a reasonable amount of discrimination towards queer people comes from transport staff. Many people responded to the survey with stories of being misgendered by the bus driver (e.g. a friendly “good morning sir” to a woman as she got on the bus). Most queer participants (81%) agreed that some specific diversity and inclusion training about the queer community could promote safer journeys for queer people.

3. Stop and station design

Nearly all the queer participants (90%) agreed that stops and stations that were well-lit would help them to feel safer while waiting for their bus or train. We also need to think carefully about how we design stops and stations, as the literature tells us that trans and gender nonconforming people can feel exposed (especially at bus stops) while waiting for services [1]. And the survey results show that a significant amount of discrimination and harassment happens here.

4. Walking routes to and from public transport

Most queer participants (91%) said that improving the safety of their routes to and from public transport would increase how safe they feel overall when using public transport. Planners should work to create safer routes to and from public transport but should do so in a nuanced and place-specific way. This is important as traditional crime prevention through environmental design principles have been criticised as being inappropriate for historically marginalised groups who are harmed by the constant surveillance they experience in public spaces [2],[3]. Updating crime prevention through environmental design principles which are appropriate for queer communities is an area of future research for planners which will help improve the overall experience of public transport.

5. Inclusive signage and messaging

A final opportunity for promoting queer safety on public transport is being deliberately inclusive with public transport signage and messaging. I love the approach taken by Transport for London, it’s subtle and serves a purpose other than directly promoting diversity and inclusion. Seeing yourself reflected in the space around you is an important factor in feeling welcome and accepted in public places.

And here’s a more local example from Wellington which is very loud and proud!

Public transport is a critical tool in our quest for a low-carbon future, however, we can’t hope to get there if we intentionally or unconsciously exclude part of society from the journey. The good news though, is that inclusive access tends to benefit everyone. For example, public transport that runs more frequently and into later hours benefits everyone. Queer people just get to “double dip” for safety benefits too.

[1] Azzouz, Ammar, Pippa Catterall, Matthew Dillon, and Mei-Yee Man Oram. 2021. Queering Public Space: Exploring the Relationship between Queer Communities and Public Spaces. (University of Westminster and Arup). https://www.arup.com/perspectives/publications/research/section/queering-public-space

[2] Cunningham, Anne. 2022. Safer Cities by Design: How better urban form can lead to safer and more vibrant city centres in Aotearoa New Zealand. (Wellington: The Helen Clark Foundation). https://helenclark.foundation/publications-and-medias/safer-cities-by-design/

[3] Lubitow, Amy, Miriam J. Abelson, and Erika Carpenter. 2020. "Transforming mobility justice: Gendered harassment and violence on transit." Journal of Transport Geography 82: 102601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2019.102601

Interesting, thanks!

One question: what was the nature of the discrimination? Misgendering is often accidental. I don't think it's discrimination unless it's deliberate, right? Were there other types of discrimination?